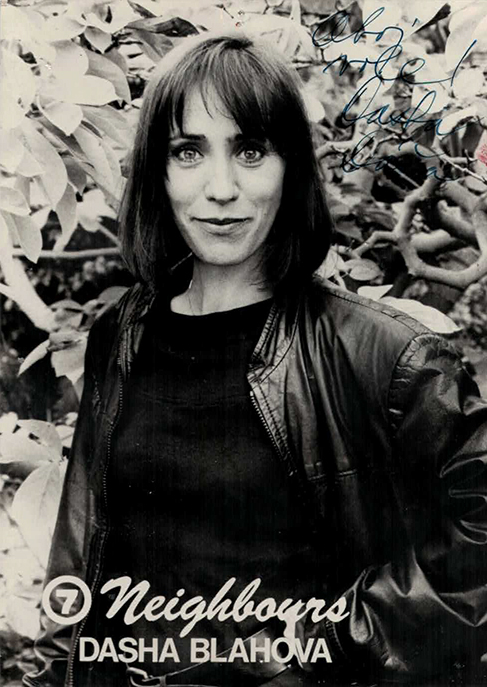

(Photo: Věra Chytilová and Dagmar Bláhová. Photo courtesy of D. Bláhová.)

Tell me about The Apple Game (Hra o Jablko, dir. Věra Chytilová, 1976, Czechoslovakia)…

Well the film is now a Czech classic and I use the film in FAMU (Film and TV School of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague) in the Masterclass, every year we screen the film and have discussions with students which is very interesting because it’s been so many years and the film is still alive. Students still show a strong interest and see the fresh ideas in the film, which is very surprising for me.

Věra passed away five years ago now; she used to be Head of the Directing Department at FAMU and was a very inspiring teacher for students. The Apple Game was my second film and there was something special about it, something Věra did in all her films from that time – she would see, or feel a moment and she filmed it. So the script of The Apple Game was something that was almost completely changed towards the end of the filming. Jiří Menzel and I were improvising a lot, which was a very different kind of work to what people were used to. That was very special work for me.

Dagmar Bláhová and Jiří Menzel in The Apple Game

After that I did 40 years in the film industry here in the Czech Republic and in Australia. I never experienced such kind of work as with Věra. She was one of those directors we call ‘intuitive’, but always down to the core, down to the point where she wanted to say something. She was a female director who was celebrated in Europe, there weren’t many at that time. Of course Věra, as a woman, always orientated on the female agenda, which was important in everything she did. The Apple Game was forbidden, and still no one can understand why – but in late ’70s Czechoslovakia under communist rule, a scene such as ‘giving birth’ couldn’t be shown on the screen. The film was shown in Chicago, receiving first prize at the Chicago Film Festival, but it took about three years before it was shown in Australia. Věra always had to fight for her films to be shown, because she was an unorthodox filmmaker, politically, aesthetically and as a woman. Because of this she is very inspiring until now. Students are still fascinated by her films, and it’s a part of the curriculum here at FAMU; her films are quite special.

How did this form your identity as a female actress?

Today the word feminist has different connotations. I would never say I’m not a feminist – I’m always behind women and equality because I was born like that. And due to growing up in a communist country where women had two jobs, including staying at home to bring up the kids. Basically this left an imprint on me and informed the collaboration with Věra, who became my friend.

Actually Věra has a brother in Wollongong, and she used to come to Australia to see him from time to time. Věra and I stayed in touch throughout the years I was in Sydney. Her brother was older than her, so hopefully he is still there. We used to know each other and see each other quite a lot. In those times Věra came to Australia several times when on her way to Asia to visit film festivals, during communist times. So we stayed in touch most of the time.

Traps (Pasti, pasti, pastičky, dir. Věra Chytilová, 1998, Czech Republic)! The original synopsis was written in Prague, and then I continued writing the script in Australia, funded by the Australian Film Commission. I then brought it back to Prague and we filmed it. The whole process of making this film took probably 20 years. The film even took a break in Věra’s brother’s wardrobe in Wollongong for some time.

Our festival theme this year is “Spring”, commemorating the 50-year anniversary of the Prague Spring. Can you tell me about that day in 1968?

I was 18 years old that year and the day before the invasion was the first day I could travel outside of the border. So I went to Paris, and I was at Sacré Cœur when I heard a Czech anthem being sung, so I went to Czech Airlines and was told that we had been occupied. My friend and I couldn’t speak French so we flew to London immediately. In London the Czechs were gathering in the student houses waiting for news and no one knew if they could return home. At that time I was in my first year of DAMU (Theatre Faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague). So I decided I would go back and study performing arts. I was living in Prague and there were Russians living in hotels around us and in tanks opposite our college. We tried to talk to them but the truth is those young soldiers had no idea where they were and what they were doing. There’s a lot of new information coming out even now about the suppression of the Prague Spring, and who did what and whose fault it was, obviously history shows a different side.

How did your immigration to Australia come about?

Dagmar Bláhová as Maria Ramsay in Neighbours. Photo courtesy of Linda Studená.

One day I went to Paris for an engagement at the National Theatre and I didn’t come back. I went to Sydney to be with my husband at the time who was an Australian Slovak, so it was a little easier for me as a migrant in Australia. I went to Belvoir St Theatre where I met Noni Hazlehurst, who suggested I meet her agent Bill Shanahan. French distributor Gaumont had kindly given me a copy of The Apple Game on 16mm, which I had taken with me under my arm. It was 1980s Australia when I showed The Apple Game to Bill – he said that Australia wasn’t ready for films like that. Bill then sent me to A Country Practice, which I did, and then Neighbours followed – where I was the first foreign actor with an accent who had a lead part in an Australian series. I played Maria Ramsay for 150 episodes.

After I returned to Prague we played Monology vagíny (The Vagina Monologues) for 15 years, we just finished this summer. I translated Eve Ensler’s original play and produced it. Usually different women would play this every time, but we had the same three actresses play in the one cast. We played all over the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

Back in Sydney I also directed a play at the Opera House called Forbidden Fruit by Christina Rossetti, and Marina at the Seymour Centre – this was a play about Marina Tsvetaeva, a Russian poet during the Russian Revolution and later an emigrant to Europe. This was a continuation of my work in a feminine tone, or note. Your mum (Uljana Studená) did the stage design for this show – she left Goose on a String Theatre (Divadlo Husa na Provázku) in Brno (Czech Republic) and immigrated to Australia with you and we worked on this show together in Sydney. It’s all connected.

The Apple Game screens at ACMI on Wednesday, 12 September at 9.15pm.

Traps screens at ACMI on Wednesday, 26 September at 8.45pm.

Both are presented in partnership with the Melbourne Cinémathèque. Admission is via Cinémathèque membership.