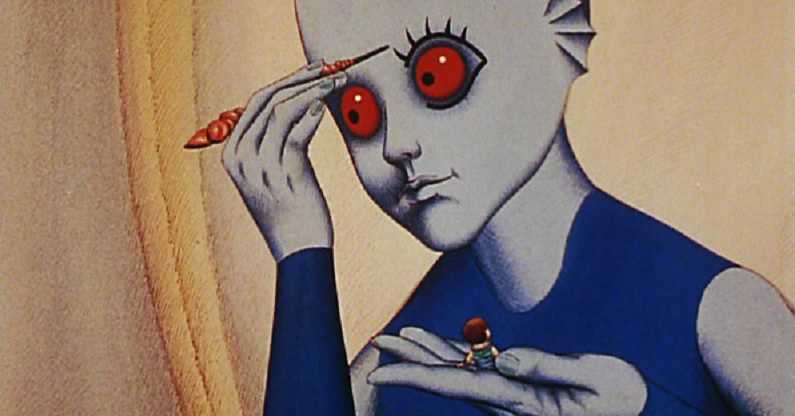

I recall fondly the first Czechoslovak film I ever saw – René Laloux’s French/Czechoslovak hybrid Fantastic Planet (1973, pictured above). It was a film I’d been itching to see ever since I stumbled across its enigmatic original trailer. An animated feature set on a distant planet, the film quickly seduced me with its crisp visuals and psychedelic jazz-funk soundtrack. It’s one of those special films, the ones that remind you that cinema really can be that spectacular, and it remains a firm favourite.

It wasn’t long before I was fortunate enough to see another Czech masterpiece, Alice (Jan Švankmajer, 1988). My childhood fascination with Lewis Carroll’s classic novel lead me to seek out its many filmic adaptations, but Švankmajer’s Alice stood out from the rest. Half stop-motion animated, half live-action, the film captures the fantastic particulars of Wonderland but reimagines them in surreally literal scenarios.

These two films, though utterly different in design, share an aesthetic. They are animated in detailed ways that I had never seen before and seem to push boundaries that I never even realised were there. They exist in utter defiance of convention. This, I would later learn, is emblematic of Czech and Slovak cinema – a cinema which seems to go where none have gone before.

My path into the world of film criticism was an admittedly unconventional one. I began not with writing but with podcast production for Triple R, working with none other than CaSFFA’s Artistic Director, Cerise Howard. I mention this because I have always had an affinity for sound, its shape, its effect. Though the visuals of Czech and Slovak cinema are often delightful, it is the soundscapes that draw me into those worlds. From the almost-but-not-quite-disembodied narration in Alice to the mockingly regal trumpeting in Daisies (Věra Chytilová, 1966), Czech and Slovak cinema proves that it’s about more than pretty pictures.

One of my initial concerns about being a CaSFFA juror was that I simply had not been exposed to enough Czech or Slovak cinema (particularly the latter). Luckily, thanks to some hand-picked recommendations from Cerise, I was able to dive into a whole range in the lead up to the festival. My experience may be limited, but what I have seen is quite diverse of genre – from steampunk to sci-fi to comedy-satire. I laughed at The Firemen’s Ball (Miloš Forman, 1967), was charmed by Closely Observed Trains (Jiří Menzel, 1966) and wonderstruck by The Fabulous Baron Munchausen (Karel Zeman, 1962). My previous encounter with a film by the latter director was 1958’s An Invention for Destruction, which is a similar visual treat. Both films are hybrids of animation and live-action, using a range of techniques – including stop motion and etch-lines drawn onto physical sets – to blur the lines between what is real and what is fantasy.

These films not only provided me with some historical context, they whetted my appetite for the films I will soon be treated with at the festival. If Zeman could create something so contemporary more than 50 years ago, I can’t wait to see what will be envisioned by the Czech and Slovak filmmakers of today.

Faith Everard is one of three members of the Australian Film Critics Association who will judge the Best New Feature Film at this year’s CaSFFA. Her AFCA colleagues Stephen A Russell and Jaymes Durante will be introduced here in coming days, with all set to contribute another blog post during the festival as well.